The Story of ADUs in Chicago and Why They Matter Now

Walk down almost any Chicago alley and you’ll see traces of the city’s hidden housing history: old garages with second-story windows, rear buildings tucked behind brick two-flats, basements with separate entrances that clearly once housed families. These aren’t anomalies. They’re reminders of a time when Chicago quietly embraced a form of housing we’re only now rediscovering, Accessory Dwelling Units, or ADUs.

For decades, ADUs were pushed underground by law. Today, they’re stepping back into the spotlight as one of Chicago’s most promising tools to address housing demand, affordability, and property value. To understand why ADUs matter now, you have to understand where they came from, why they disappeared, and how they’re returning carefully, deliberately, and very much in Chicago’s own style.

(1) What’s an ADU, Really?

At its core, an Accessory Dwelling Unit is a second, independent home on a lot that already has a primary residence. It’s not a room share, not an Airbnb, and not a temporary structure. An ADU has its own kitchen, bathroom, and living space, and it’s meant for long-term occupancy.

In Chicago, ADUs usually take one of three forms. The most familiar is the interior conversion unit, a basement garden apartment or an attic turned into a small but complete home. These exist all over the city, often quietly rented for years despite being technically illegal.

Then there are coach houses, detached structures typically built in the rear yard, often replacing or sitting above a garage. Coach houses are deeply rooted in Chicago’s architectural DNA, dating back to when carriage houses lined alleys throughout the city.

Finally, there are granny flats, a casual term that usually refers to any small ADU created for family members. Legally, Chicago doesn’t treat these differently, but culturally, they highlight one of the most human uses of ADUs: housing aging parents, adult children, or extended family while maintaining independence.

What ADUs are not is equally important. In Chicago, ADUs cannot be sold separately, and they cannot be used as short-term rentals. They are meant to add stable housing, not transient lodging to neighborhoods.

(2) A City That Once Embraced ADUs, Then Didn’t

Chicago didn’t invent ADUs, but it perfected them early. Before the mid-20th century, coach houses and basement units were common, practical responses to a growing city. They allowed families to live close together, provided income for homeowners, and added density without altering neighborhood character.

That all changed in 1957, when Chicago banned new ADUs outright. The reasons were many, concerns about overcrowding, parking, and neighborhood change, but the result was simple: an entire housing type was frozen in time.

For more than 60 years, no new ADUs could be legally built. Existing ones survived only if they were grandfathered or ignored. Many fell into disrepair. Others continued operating quietly, creating a gray market of “illegal garden units” that housed thousands of residents without formal protections.

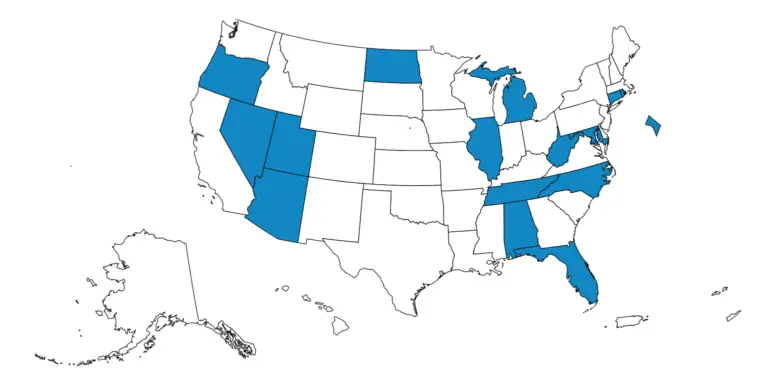

By the 2010s, cracks in the system were impossible to ignore. Housing costs rose. Vacancy tightened. Families needed flexibility. And cities across the country from Portland to Minneapolis, began re-embracing ADUs as a solution.

Chicago moved cautiously. In December 2020, City Council approved an ADU pilot program, limited to five zones across the city. Permits became available in May 2021, allowing homeowners to convert basements or build coach houses, if they were lucky enough to be in the right area.

The pilot didn’t flood the city with new units, but it did something more important: it worked. Roughly 400 ADUs were permitted, proving that residents wanted them and neighborhoods could absorb them. That success planted the seed for something bigger.

(3) What’s New. The 2026 Turning Point

The real shift comes on April 1, 2026, when Chicago’s ADU rules expand beyond the pilot zones and become permanent.

Under the new ordinance, all multifamily residential zoning districts (RT and RM) across the city excluding downtown will allow ADUs as of right. That alone expands eligibility by roughly 135% compared to the pilot program.

Single-family zones are more complicated. In those areas, ADUs are not automatically allowed citywide. Instead, alderpersons can opt in specific blocks or areas of their wards and set local conditions. This was the political compromise that made expansion possible.

The result is a very Chicago outcome: ADUs are broadly legal, but locally controlled. One ward may welcome them enthusiastically. Another may allow them slowly, block by block, with caps and conditions.

(4) How Many ADUs Can You Have?

For most owners, the answer is simple:

On 1–4 unit properties, you may add a single ADU, either an interior unit or a coach house, but not both. That means a single-family home could gain one backyard coach house, or a three-flat could legalize a basement unit.

Larger buildings can add more, but with strings attached. Buildings with 5–7 units can add up to two ADUs, and 8–10 unit buildings up to three. Once you reach those thresholds, affordability requirements kick in, typically requiring at least one ADU to be offered at a regulated rent tied to area median income.

For 11+ unit buildings, ADUs can equal roughly 33% of the existing unit count, again with affordability obligations.

Across the board, only one coach house per lot is allowed. Interior ADUs require the building to be at least 20 years old, a safeguard meant to prevent immediate overbuilding but one that most Chicago properties already satisfy.

(5) The Rules That Shape the Story

ADUs may be encouraged, but they are not casual projects.

Perhaps the most important rule is aldermanic control. In RS-zoned areas, alderpersons can require owner-occupancy, cap how many ADUs are allowed per block per year, or mandate additional approvals. In some neighborhoods, you may need to live on-site to add an ADU. In others, you may need to wait your turn.

Then there are building codes. ADUs must meet modern standards for safety, light, ventilation, ceiling height, and egress. This is especially relevant for basement units that were previously rented informally.

Coach houses bring additional complexity. As new construction, they may trigger labor and workforce requirements, which can increase costs and limit contractor availability. Timelines and budgets need to be realistic.

And finally, Chicago is clear: no short-term rentals. ADUs are meant to be homes, not hotel rooms.

(6) Why ADUs Matter. Beyond the Rules

It’s easy to get lost in zoning tables and permit checklists, but the real reason ADUs matter is what they make possible.

For homeowners, ADUs can mean financial stability, extra income that helps cover rising taxes, insurance, and maintenance. For landlords, they’re a value-add strategy that doesn’t require buying new land or tearing down buildings.

For families, ADUs offer flexibility. A parent can age in place. An adult child can live independently but close. And when life changes, the unit can shift from personal use to rental income.

For the city, ADUs are a form of gentle density. They add housing without overwhelming infrastructure or radically changing neighborhood character. One unit at a time, they help ease pressure on a tight housing market.

(7) Tips and Opportunities for Property Owners

If you’re considering an ADU, the biggest mistake is assuming it’s simple. The smartest owners approach ADUs like investors.

Start by confirming eligibility, zoning, ward rules, and timing all matter. Then run the numbers honestly. Interior conversions are often cheaper than coach houses, but both require meaningful capital.

Hire professionals who understand Chicago. Architects, contractors, and advisors familiar with local permitting can save months of frustration. And plan for time: permits take longer than standard renovations.

Finally, think operationally. One more unit means one more lease, one more resident, and one more set of expectations. Good management turns ADUs from headaches into assets.

(8) How Three Pentacles, PLLC Can Help

At Three Pentacles, PLLC, we view ADUs not as isolated construction projects, but as strategic decisions within a broader real estate portfolio.

We help property owners understand ward-specific rules, evaluate feasibility, coordinate with design and construction teams, and align ADU projects with long-term investment goals. In a city where regulations vary block by block, informed guidance is often the difference between a stalled idea and a successful project.

Chicago’s ADU story is still being written. Starting in 2026, coach houses and basement units will no longer be relics of the past, they’ll be tools for the future.

If you look closely, the opportunity may already be there: a basement waiting to be legalized, an attic waiting to be finished, a backyard waiting to be reimagined. ADUs won’t solve every housing problem, but one well-planned unit at a time, they can change the trajectory of a property and maybe even a neighborhood.

In Chicago, that kind of quiet, incremental change is often how the most lasting progress is made.

(9) About the Author, Arthur R. van der Vant

Arthur R. van der Vant is a real estate attorney, investor, and advisor who focuses on the intersection of law, housing policy, and long-term property strategy in Chicago. As the principal of Three Pentacles, PLLC, Arthur works closely with landlords, developers, and small investors to help them navigate complex regulatory environments while building durable, value-driven real estate portfolios.

Arthur R. van der Vant is a real estate attorney, investor, and advisor who focuses on the intersection of law, housing policy, and long-term property strategy in Chicago. As the principal of Three Pentacles, PLLC, Arthur works closely with landlords, developers, and small investors to help them navigate complex regulatory environments while building durable, value-driven real estate portfolios.

Arthur’s perspective on ADUs is shaped by both practice and experience. He understands ADUs not as abstract policy tools, but as real-world projects that live or die based on zoning nuances, permitting realities, financing constraints, and neighborhood politics. His work often involves helping clients evaluate whether an ADU makes sense before money is spent, analyzing feasibility, risk, and long-term return rather than chasing trends.

Beyond individual projects, Arthur closely follows Chicago’s evolving housing landscape, particularly reforms like the ADU ordinance that signal deeper shifts in how the city thinks about density, affordability, and neighborhood preservation. He believes ADUs represent a uniquely Chicago opportunity: incremental, locally grounded, and capable of unlocking hidden value in existing buildings without erasing the character that makes the city’s neighborhoods work.

Arthur writes and advises with one guiding principle in mind: real estate success comes from understanding both the rules on paper and how they operate in practice. As ADUs become a permanent part of Chicago’s housing equation, his goal is to help property owners approach them not as experiments, but as intentional, well-structured investments built to last.